In and Out of Africa

Africa in unrest

Mamfe looked very different in the daytime. It had a 'lived in' look about it although a few coats of paint and some window glass and it could have been a small town anywhere in Southern Europe. We left Mamfe and started along the Mamfe to Kumba road. According to the Michelin map this was a super-duper improved road, bright red with thick black border. We expected a fast trip to Kumba.

In addition to the inevitable copy of 'Shoestring', almost every traveller (other than those on tour trucks who did little navigation) also had the Michelin maps of Africa. Many people, like us, were also filling in their route as they went with a cross for each campsite. The Michelin maps cover a large area (three sheets for the whole of Africa) but are all there is and are reasonably accurate for such a small scale. It must be very difficult to keep these maps up to date and I suspect they rely heavily on each country to give them current information. Whatever the mechanism it somehow leads to 'wish roads'. The government wishes a road were there. They tell Michelin where they think a road should be and instantly the road exists!

|

| Morning in the Cameroun Jungle |

|---|

Inevitably the approach to the bridge was slippery with thick mud and we would slide, barely under control, onto the bridge. Mud covered logs provide an almost frictionless surface suitable for ice rinks or non-stick cooking equipment. As we slid across the bridge there was always a heart stopping moment before the front wheels gained enough traction to pull us up the opposite bank to safety.

In stark contrast to the barren Sahara and the pasturelands of Nigeria the dense jungle is full of life. As the morning mists rise gently to meet the warming sun the monkeys start to jabber and crash about in the trees. Huge black and white hornbills embark on their daily cruise across the sky, like frigates of the air. The air gradually saturated with the sound of cicadas and mysterious unseen birds.

After a couple of hours of unbroken jungle we came across a gateway to a well tended garden. This was the first place we had been able to stop since Mamfe so we pulled over for a late breakfast of soup with dried potato mixed in for extra body. We had almost finished when the owner wandered past looking for a lost goat. He came over to make sure that we weren't leaving any mess and stopped to talk. He used to be a mathematics professor at the university in the City. After a while he felt that it was immoral to continue earning a highly inflated salary when so many of his countrymen were living in poverty. So he sought out a suitable section of jungle and started an experiment in organic farming methods using indigenous plants. He had been doing this for over 10 years and his garden was now very well tended and healthy. A cultivated oasis in contrast to the rampant jungle surrounding it.

The local attitude to crops is simple. Clear a patch of jungle, live there until you have depleted the soil and things no longer grow easily, then move on to another section of jungle leaving the last bit to regenerate. This method has worked successfully for thousands of years. With modern population densities this type of agriculture can no longer be sustained. When his research is finished our friend intends to start educating the people in new methods of farming for the good of all. Amidst so much well intentioned yet often inappropriate foreign aid, it is refreshing to see someone doing useful work to help their own people.

A little further along the jungle road we came across something completely unexpected. A wish road come true. Wide, smooth, new tar seal! As if this wasn't enough of a surprise we were overtaken by a brand new Hyundai saloon car, clear plastic still covering the seats and no number plates! This made a change from the ubiquitous Peugot 504. Even more surprising the car was driven by an Asiatic gentleman. He was as surprised to see a Safari prepared Landrover as we were to see a brand new Hyundai. The road was being built by a Korean construction company called Daewoo, one of four international companies contracted to build the Mamfe to Kumba road. His was the test car and the road was as smooth as an autobahn. The bad news was that the road was far from completion having been beset by problems common to tropical road building. Of the original 4 companies two, including the French, had dropped out due to lack of expertise in the tropics.

So, even when the Koreans finish their section there will be nothing to join it too. We carried on. Sometimes racing along smooth tar, sometimes struggling through the narrow, muddy, jungle track. Whenever the road passed through a village the huts were simply moved back outside the path of the road and the road was driven straight through the village. This looked particularly odd where the road was in a cutting or on an embankment. If you wanted to visit someone on the other side of the road you had to climb down a shear 20 foot drop, cross the road and climb another on the other side!

No planning meetings or environmental research, no endless petitions about real estate values and the quality of village life here. No committees, no public enquiries and definitely no compensation. Just plow the road right on through! There are many of these prestigious new tar roads being built in various countries, often with massive foreign aid being pumped into this project. Unfortunately there is never any money set aside for either road maintenance or training. The construction company's job is over when the road is finished and the aid stops when all the publicity photographs are taken. This leaves local untrained labour to maintain the road. We saw some roads, even though only about 5 years old, which had virtually reverted to tracks. All that has been achieved is to split a few villages in two. All too often we could see the tattered remnants of previous aid projects where a huge bucket of money had been used up and forgotten when a perpetually dripping tap would have been more appropriate.

Eventually we arrive at Kumba. The main street was liberally sprinkled with potholes the size of dinner tables. Or should I say the pothole running through the centre of town had a few small strips of tar within it. The decay which is modern Africa became more noticeable as we travelled further into the interior. In the middle of the road, well into the town, there was something rather odd and vaguely disturbing. Throughout the trip we had seen abandoned, stripped and apparently burnt out vehicles on the side of the road. But here, in the main street of Kumba, were two burnt out trucks. It was as though they had stopped in the middle of the road and been abandoned, spontaneously bursting into flames before they could be reclaimed. Very careless we thought and it must have happened very recently as the trucks had not yet been stripped bare to the chassis. There were more of those funny black tyre sized rings in the middle of the road and the soda factory had also been abandoned and burned to the ground. At this point we began to make a connection with the 'troubles in the South'.

We headed towards Douala with a sense of foreboding. There is a tar sealed road from Kumba to Douala with only a few potholes and the inevitable road side vendors. Throughout Africa, there are people on the side of the road selling local produce fruit, vegetables etc. Often they sell animals for food, both dead and alive, chicken and monkey being a favourite although we were offered turtle and other exotic creatures. Vendors with souvenirs were unusual in this part of Africa, although commonplace in East and Southern Africa). On the outskirts of Douala there were people on the roadside bouncing what looked like big rubber balls. Eventually curiosity got the better of us and we pull over to investigate. This particular vendor spoke quite good English and was as curious about us as we were about his bouncy things. He explained that they are made out of natural (unvulcanised) rubber from the local trees and gave us one. All he wanted in return was our address so he could write to us and improve his English. We have yet to received any correspondence from him.

The 'ball' was amazing, about 25 cm in diameter and very bouncy. It appeared to be made by wrapping a really long rubber band into a ball shape - like a ball of wool. Over the next few days it slowly deflated and I wondered if there was some hideous rotting animal bladder deep inside which was not completely airtight. I cut it open my worst fears were realised if not surpassed. There was indeed a great length of rotten animal entrails in the centre. Nevertheless it was a free gift from an African. Acts of generosity like this made the trip worthwhile and will hopefully still remain in our memory after the people with hands out shouting "Cadeux, cadeux", "Give me one thing", "Toooureest" and "Donnez-moi Bic" have been forgotten.

In Douala 'Shoestring' states that the best place to stay is the 'Mission Catholique'. It is very clean with gleaming ceramic toilets, hot water, a swimming pool, air conditioning, a beer machine and meals. It also says you can leave baggage safely (high recommendation indeed). When we showed the priest the references to his establishment and he nodded his head in agreement. Unfortunately the meals are fully booked for tonight and the beer machine is temporarily empty. Oh well, we can go into town. "Oh no", they say -"it really isn't safe at night, especially after the riots". The riots had been less than two weeks ago and the town was still simmering with discontent. The Spanish robbers would have heard the BBC correspondent describe them as some of the worst riots he had ever seen in West Africa. The burned out car visible from the bedroom window was a testament to how close this had been. Much later we found out that there had been also been rioting in Yankari less than a week before we had arrived there. We were very close to getting caught up in a dangerous situation. Not even the Spanish robbers knew how much closer we were to get before the trip was over.

The truck was safely parked in a walled courtyard and we made our little meal in the open air next to it before retiring to a blissful nights sleep in an air conditioned room. This was one of the very few nights we didn't sleep either in the back of the Truck or in our roof tent. It was safe to leave the truck alone here, riots or not, as the entrance to the courtyard was small and one of the guards spent the night lying across the entrance way!

Douala was to be our first mail drop. There is nothing quite like receiving mail on the road. We had arranged to have mail sent to the American Express office, rather than the usual Poste Restante at the Post Office as we assumed there would be less mail to wade through to find our letters. This was true, mostly because there were only two letters waiting for us. Much later we found out that several letters had been sent, some finally arriving back in New Zealand over a year later. At the time we felt forgotten and left Douala feeling unloved and unwanted. Not even a pastry from the French bakehouse could cheer us up.

The roads between Yaounde and Douala are pretty good, there was even a multi lane highway for a short while, so we made fair time. It had been a rush to get to Cameroun while our visas were still valid for entry. Now we were here Fiona's visa was only valid for a two week stay. Once again we were in a hurry to get to the next country. Even if the visa had been valid for longer it would been sensible to get away from the main focus of the Rioting. But first we had to get visas for the Central African Republic from their embassy in Yaounde. This should, of course, only take a short while.

As anyone who has been on a trip like this will know, visas are a major headache. It is essential that your paper work is in good order. This will help you avoid paying bribes, being thrown in jail, waiting for weeks at a border etc. It is possible to get visas for the most of the countries in London, Paris or any major capital city. Many of the visas have a date by which you must enter the country. Which means you can only get about three months worth of visas in advance. In practise it is nearly impossible to coordinate all your visas before leaving and many of them will be cheaper in the neighbouring countries than they would be from a non African nation. Crossing borders are major events in any trans continental trip. Visas, the lack/cost/availability of and local currency the obtaining/lack of are high on any third world travellers list of priorities. Just below food and diesel, just above beer and about the same as finding a decent toilet.

So we head into Yaounde using the inevitable 'Africa on a Shoestring' map and get hopelessly lost trying to find the one campsite. At least we knew there had been a campsite once and the facilities it may have offered in the past. The map took us extremely close, but not close enough though and again we needed local help to show us the way. There are so many stories of someone showing you the way into their den of thieves and murdering you that we always found this a rather nerve wracking experience. In reality we never had any trouble and only very rarely did the kind people ask for anything in return. On the rare occasions that they did this was usually clear before hand.

In this case the boy in question was a member of the mission where the campsite was situated and helped us for free. Even though we took him out of his way. Thinking back we probably experienced this type of helpful behaviour more in Cameroun than almost anywhere else (except possibly Zaire).

When we found the campsite the African lady running the 'Foyer International' tried very hard to persuade us to take a room, rather than camping, as it was much safer. Then the French missionary running the place also told us how dangerous the campsite was and that many people who camp there get robbed and beaten up. He also stressed very strongly that we shouldn't leave the mission after dark, even to go to the restaurant around the corner. Recently a Dutch couple didn't head this warning and were beaten up severely in the alley way by men with large wooden staves and lost some money and travellers cheques. The story doesn't end here though. When the lady received her replacement travellers cheques a couple of days later she went to the bank to change some money and noticed the man in front of her in the queue cashing her stolen cheques!

The campsite was empty and we began to feel a little insecure. We were caught in a dilemma. Do we rent a room and leave our Landrover outside unattended for people to pilfer from at will, or do we sleep on the Landrover and get beaten up and robbed anyway!! Fortunately two Americans called Eric and Brian arrived on motorbikes. They were also warned about the danger. "Yah" said Eric, "No problem". Grinning they produced razor sharp machetes from their panniers. We were starting to feel safer already! They hooked up their mosquito nets between a tree and our Landrover. Surely they would be murdered first and make enough noise for us to wake up and run away! A little later two Dutch guys arrived, also on motorbikes, and the campsite started to feel a lot safer.

The night passed without incident and in the morning we were greeted with the sight of a pale looking white man jogging around the mission compound. This was strange behaviour indeed in the already 30 degree heat and high humidity. It was no surprise that he was sweating profusely and out of breath. He was even more sweaty and out of breath after the second lap!

We set off early to the C.A.R. embassy to get the visas. My visa, for a British passport, was easy. Fiona's, for a New Zealand passport, was not. Before they would issue her visa we had to take a telex to the telex office somewhere else in the city and send it to Bangui for confirmation. The telex was prepared by the embassy staff 'while you wait'. Where waiting is an activity which is never less than an hour. In fact several hours elapsed before they had typed out the four line telex. Now we had to take the telex to the office in town ourselves, pay for the telex, collect the reply later and take it back to the embassy. This seemed a strange way of doing things, surely the embassy had its own telex machine? However this is Africa and questioning these things only leads to trouble. Now we had to find the telex office. How can do you set about finding a telex office if you don't know enough French and when trying to do the international sign language for 'telex office' could easily lead to physical damage. Fortunately for us there was a local who also needed to send a telex for a similar visa so we shared a taxi with him.

The telex office was a shiny air-conditioned building with new carpets, plate glass windows and comfortable chairs. It stood in sharp contrast too the old decaying and forgotten buildings surrounding it. We managed to send our telex with no problems. The reply would probably be ready tomorrow afternoon. Our friend from the Taxi had to wait an extra day for his. The Telephone section of the telecommunications building was next door and just as opulent. The walls were lined with small phone booths. The telephones were the very latest in modern technology and accepted 'smart' cards with a little computer chip in them. There was only one place in the Town where you could buy the cards, a counter in the same room as they were the only phone boxes in the country which could accept them. Thus completely offsetting the convenience value of phone cards.

Back at the campsite we swapped travel stories with Eric and Brian. They had been intending to take a leisurely ride across the Saharan piste, taking in the ambience of the desert. They had however committed the grave error of not checking their visas correctly. Their visas had been issued on the same day from the same office and they had entered Algeria together. Eric had plenty of time left on his visa, Brian however only had another day. To make matters worse Eric had been asked an unfortunate question by the border official "What you think, Saddam Hussein?". Eric replied, "He's a fanatical lunatic". This was, of course, the verbal equivalent of pouring diesel over the mans uniform and the remarkably lenient Algerian official said. "If you aren't across the desert by tomorrow I'll have you thrown in jail". They raced through the desert like Paris/Dakar veterans and reached Niger with precious little time to spare!

They had other problems, like bald tyres. Their motorbikes where trail bikes designed for the American market. They had unusual sized wheels and the tyre patterns designed for use on Californian highways. The tyres hadn't survived a race through the Sahara. By chance there were two tyres of the correct size at the mission, abandoned by a previous traveller as being unfit for use. They had far more tread than the ones currently on the bikes and they immediately set about fitting them.

In Agadez they had been persuaded to buy a Tuareg sword. The Tuareg had been noted for their ferocity and the quality of their blades. They would never have gained this reputation using this particular sword. It had already shattered from the vibration of the motorbikes.

Eric and Brian left later that day. Their motorbikes were fast, small and mobile. When they wanted to stop for the night they would just decide where to stop and machete themselves a path into the bush large enough for two motorbikes and two people. We had to find a ready made flat Landrover sized area preferably hidden from the road. If there was an obstacle blocking the road they could push their bikes around. We couldn't even come close to this level of mobility and didn't expect to see them, or the much better prepared Dutch motorcyclists, again.

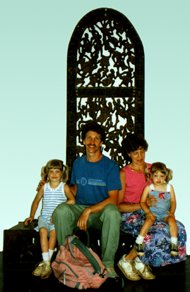

In the afternoon an American lady called Milena and her two small children came over to talk to these strange travelling folk. After speaking to us for a while she decided to fetch her husband, Dale, who would also be interested in talking to these mad foolish people driving across Africa in a Landrover.

Dale turned out to be the mystery jogger! He was working at the mission hospital for a month to replace the normal (African) surgeon who was attending a conference in America. Dale feels he should do something every year for the good of humanity and to broaden his, and his families, horizons. They had spent a month the previous year in Zimbabwe doing similar work. Cameroun however was not quite what they expected. Yaounde is in the predominantly French speaking part of Cameroun. Dale had been told that Cameroun was bi-lingual and their lack of a French would be no problem. In a way this was true. Most of the people Dale had to treat couldn't speak French either, let alone English. The facilities and general level of hygiene were also different from those in Zimbabwe. The conditions in an average African hospital would have made even Florence Nightingale throw down her lamp in horror.

I mentioned in passing how dangerous the campsite was. It was getting late now, no one else had appeared and I was beginning to get mildly concerned. Dale suggested we camp outside the house they were staying in. This was also within the mission complex but, like the more affluent houses throughout Africa (where affluent is a relative term) it had a walled compound with broken glass on the top. Not only that, they had a cook and 'guardian' supplied.

| Stormclouds Over Cameroun |

|---|

|

With the truck safe within a locked compound we took the opportunity to walk around the local market. Ever since the robbery in Spain we didn't like to leave the truck unattended for very long and usually one of us would stay with the truck while the other went in search of food. It was a welcome change walking round the market together, experiencing the sights and the smells. The strange piles of goods. Unknown powders and strange spices. Vegetables stacked in little piles, the price in chalk next to them. Little bowls of insects... The market was crowded and noisy with the sound of people haggling over price or inspecting the goods. The rancid smell of the dried fish was becoming oppressive so we decided to go back around once more and buy some less smelly supplies. I noticed a guy wandering just in front and to the left of me holding a 200 CFA note in his outstretched hand. Strange behaviour I thought and vague warning bells were ringing at the back of my mind. A short while later he appeared again, still with the note in his hand. I had this uncanny feeling that I was surrounded. Someone hit me gently on the ear while someone else's hand tried to reach into my trouser pocket. I whirled round pushing one guy in front of a moving Taxi and found myself in the same slightly crouched stance as when I took on the baboons.

There where six or more large Africans around me. I was swearing and ready for a fight "One of you ##*$%! guys...".

Fiona however pointed out a few salient facts.

- I am a peaceful man and have no experience in fighting.

- I am greatly outnumbered.

- I haven't bought the machete yet.

- I have no wish to share blood products with anybody here.

This information was conveyed by a simple phrase like 'Don't be stupid'. Overcome by the logic of this I backed across the road. They didn't try to follow us. There was a level of tension and aggression here for which I was ill prepared. The jelly like feeling in my knees was also an unusual experience.

This spoiled the market for us and we went to the modern, safe and sanitised supermarket instead without feeling at all guilty. We would visit the supermarket several times during the next two weeks but we never went back to the market.

Outside the supermarket there were some people selling local delicacies. One man was selling little dough balls, like small round doughnuts, with an accompanying hot chilli sauce. We asked for about six. The man looked shocked and puzzled. "They are hot, hot!". We tried one and did the international sign language for 'these are really good' and the sauce was indeed very hot. He was even more surprised when we went back the next day for some more!

In the afternoon we returned to the telex office to collect the reply.

There was a reply waiting which had been there since 08:00 this morning. It said:

"Nationalities not specified - applications not processed" (In French).

The idiot at the embassy hadn't put Fiona's nationality on the telex. At least she was consistent. She had made the same mistake for the man who had shared the taxi with us yesterday. He wasn't expecting a reply until tomorrow and there was no way to let him know what had happened. The man in the telex office said we would have to go back to the embassy tomorrow morning and get the telex re-written. This seemed like an incredible waste of time, which we didn't have as Fiona's visa was rapidly running out. Fiona persuaded him to re-send the telex with the words New Zealand Citizen (in French) added on the bottom.

Each delay in getting the visa meant another whole days wait and we only had a total of two weeks in Cameroun so time was running out. We were feeling increasingly trapped and out of control. Our Nigerian visa was only a single entry one - so we couldn't go back, we couldn't go forward without a C.A.R. visa and we couldn't stay here once Fiona's visa had run out. To make our feelings of inadequacy and isolation greater we phoned home. The news was not very good. The insurance company refused to pay up after our robbery. We had apparently taken "insufficient care". We wrote back to the effect that "The money was in a locked cashbox, in a locked and hidden compartment in a locked vehicle with extra padlocks on all the doors". Short of a sign saying beware of the tiger in 10 languages I don't see what more we could have done. I suppose if we had walked around carrying the money and been murdered they would have happily paid out to our estates. I would still be interested to know what, in an insurance company's eyes, constitutes sufficient care. We had made no secret of our destination or method of travel when we bought the insurance. They were happy enough to take our money then. The other news from home was no better. There were other family problems and we were powerless to help. We couldn't even get out of this one town let alone back home.

| The Dannekers |

|---|

|

There was also a television so we could soak up the local TV culture. The programming was in a random mix of French, English and local languages. Sometimes they would swap languages during the program depending on which language the presenter felt happiest with. One night they showed coverage of roller skate racing in a blocked of street in down town Yaounde. This was treated as seriously as the Olympics would be anywhere else. Between the races they had other entertainments. One of these can only be described as contortionist breakdancing. This amazing routine involved two guys dancing in a reasonably normal break dance fashion while the leader would spin around with limbs in impossible positions or shake his legs as though they were made of rubber. During this time the commentators were describing his actions, as they would an ice dancing championship. "See him do his thing, see him flip, watch him shake". At the end the routine he hooked his legs behind his neck and wove his arms through the gaps. He was carried smiling triumphantly from the street. "They call him the man with no bones", said the commentator, "It is a name he likes".

We could also catch up with the news, although there was little mention of the riots or their cause. The reasons behind the rioting came from a semi-underground newspaper and talking to locals. The president, among other things, owns the major brewery and soft drinks bottling company. On coming to power one of his first actions was make it extremely easy to obtain a license to sell beer. As we drove through Cameroun it had seemed strange that every third house in the villages was some form of bar. Alcohol is a growing social problem throughout Africa. The president's profiteering with blatant disregard for the health and well being of the people, coupled with other economic problems, had provided a focus for the peoples anger. This also explained the burned out soda factory and delivery trucks in Kumba.

In the morning we returned to the telex office with eager anticipation. No luck. We return again in the afternoon and the man from the Taxi is looking for his reply. The Embassy in Bangui had only sent one reply which said the nationalities had been missed off both visa applications. Perhaps they assumed that Fiona and this man were travelling together, even though the Visas were for different purposes, or maybe they intended to save money by only sending one telex. As the man in the office looked in vain for a reply to our friend's telex we realised that the first reply had been indexed to our telex and he would never find a reply to the other mans telex. "Come back tomorrow" he said. We furiously tried the international sign language for "We got a reply to our telex saying that the nationality was missed out and the same thing was wrong with your telex". If this was a television game show we would have got lots of laughs but wouldn't win the car. This wasn't a TV game show and we were determined to help this man. After all without his help we would never have found the telex office in the first place. So we dragged him next door to the telephone office where the Ladies behind the counter could speak English. The first Ten minutes were wasted because they couldn't understand why we wanted to help this man in the first place. "What is your relationship to this man", "How long have you known this man". There seemed a great deal of suspicion of our motives. The idea that we simply wanted to be helpful seemed beyond them. Finally we got our message across and went back to the telex office while the Ladies behind the telephone counter shook there heads in puzzlement. Our friend finally found our original reply. He still had to resend his original telex with his nationality appended but at least he wouldn't be returning day after day in vain.

That evening, after 'Miller time' we met an American missionary called Angie. She was a quietly spoken lady who managed to keep her soft, slow Southern American accent even after 20 years in Zaire as a missionary. For health reasons the mission had recalled her to the U.S. When she returned she found the cultural change too great and asked to be sent back to Africa. There was no place for her in her Zaire, which she thought of as home, so she was sent to Cameroun. She preferred Zaire (we would understand why later) and was going there again to see her old friends quite soon. Angie was truly a remarkable woman. Among other things she had at one time decided to visit all of the missions in Zaire. To do this she had driven alone in a Landrover through some of the most appalling road conditions in the world. After all this trial and hardship she was still the most kindly spoken and caring person I have ever met. Totally and selflessly committed to her beliefs, and to her work Africa and its people.

Friday morning meant another trip to the telex office. Once again our reply had not arrived. Fiona's visa would run out on Tuesday and we had been told that they never extended tourist visas. Doom, gloom, despondency, what on earth do we do now. There was always the British Embassy, staunch and strong, empowered to protect and help Commonwealth citizens embassy in times of war, pestilence and other dire emergencies. Although our problems didn't rate as even a minor emergency on a world scale, they seemed fairly serious to us. After all, if we ended up in a Cameroun prison for visa infringements it would mean a lot more work for them. We went, sheepishly, to the British Embassy for help.